NB: This is the written work and slide images from a talk I gave as part of the fabulous Yale Book History Seminar this weekend. Thank you to the amazing organizers for a really wonderful event. We were given provocations/prompts and asked to speak for about 20 mins. I think the most compelling part is the first section and the final paragraph :). Someday, when the book is done, I’ll work this up into something a bit more formal. Our first question for a panel on the Afterlives of the Book, asked “what are the affordances of (book-like) materials, and how might scholars, archivists, and students work with them most effectively?” I felt I needed to grapple with premise of a death/afterlife before getting to affordances…

Part of the challenge of the pronouncements about the “death of X” is that they tend to be sweeping statements that ignore questions about users/readers, contexts, and economic and infrastructural dependencies. I was so delighted to hear Joseph bring up the entropy and innovation that readers introduce to book history.

Confronted with the idea of the death of the book, I might first ask “dead for whom? In what contexts?” Is the book dead for literature classes at small liberal arts colleges? No. Is the book dead for historical surveys in large public institutions? No, but it has changed. Is the book dead for beach or mountain or home reading on vacation? No. Is the book dead for those who are working to reduce non-essential expenditures? Maybe, but that might not be new. I could go on and on in this vein, but I suspect you understand that my point here is that an analysis of media technology is always wrapped up in understanding the material and social conditions of its use. Much to my delight books are a stubborn genre of media technology.

I’m a feminist literary historian who focuses on technologies of commemoration and imagination, so I tend to make my first move one of looking back. While I’m sensitive to radical shifts and breaks, I favor continuities as a political and epistemological gesture. I’m committed to the weaving work that we can do as scholars to make dependencies and relationships visible. So in response to this set of questions, my first impulse was to look back and to think again about what book history and studies of technology can tell us about this idea of the death of the book.

If we take the metaphor of death seriously, we have to think about the lifecycle of the book. Did it have a birth? Certainly we can look at the rise of the print industry, but as any medievalist or early modernist will tell you, the codex was not an exclusively print technology. While Gutenberg’s printing press pushed reproduction to a new scale in the fifteenth century, the press, moveable type, and all the rest was not the “birth” of the book. It was the birth of print perhaps, but this included an array of media formats, many of which were unbound. So the birth of the codex has to have happened at some other time.

of death seriously, we have to think about the lifecycle of the book. Did it have a birth? Certainly we can look at the rise of the print industry, but as any medievalist or early modernist will tell you, the codex was not an exclusively print technology. While Gutenberg’s printing press pushed reproduction to a new scale in the fifteenth century, the press, moveable type, and all the rest was not the “birth” of the book. It was the birth of print perhaps, but this included an array of media formats, many of which were unbound. So the birth of the codex has to have happened at some other time.

The long slow shift from the scroll to the codex is usually dated from the first to the fourth or fifth century C.E. but this raises interesting definitional problems. Late antique media forms included both the papyrus or parchment roll or scroll, and metal, wood, and wax tablets – some of which were strung together in what are described as diptychs, triptychs, or polyptychs. Paul Needham’s Twelve Centuries of Bookbindings 400-1600 suggests that the term “codex” originally referred to a set of wooden tablets bound together in this fashion and dates the oldest surviving example (a Greek/Phoenician alphabet) from 800 B.C.E.[1]

So I’m not so sure that we can point at a single book as the first, and we can’t necessarily do that for the codex either. We can say that we have an oldest surviving example that is more than 2800 years old, but that is about it. I take this longish detour in part to make it clear how difficult it would be to locate the “birth of the book” if we take a book to be something like a bound collection of writing. If we can’t locate a birth, it’s going to be hard to determine a death. This difficulty suggests that thinking about the birth/death of a thing called the book might not be the best approach.

Johanna Drucker suggests as much when she observes that ebook designers would do well to ask “how a book does….rather than what a book is.”[2] Like Drucker I tend to favor understanding media technologies as a set of formal constraints on the field of possible uses and tend to approach ‘meaning’ as something created in a dynamic process that we generally refer to as ‘reading.’ Drucker describes her approach as “the program of the codex, ” where ‘program’ refers to the set of activities that arise in response to or in engagement with formal structures. [3] I understand reading as a performative event (Drucker also describes it as book as a “performative space for the production of reading”[4]) – one where a media’s formal features and content are part of a process of co-dependent meaning/use creation that includes the reader/user and her contexts.

Drucker suggests that we think of the codex not as it appears, but as it works as a “dynamic knowledge system, organized and structured to allow various routes of access”[5] Drawing on Roger Chartier’s and Malcolm Parkes’ excellent work on histories of the book and reading, Drucker encourages us to think about the typographic and paratextual elements that shifted the “program” of the codex from one of linear, monastic reading and prayer toward scholastic argumentation between the 12th and 14th centuries.[6] We might be able to point to a complex network of formal features and practices that inaugurated uses of book technology in the late medieval period in the way we might think of it today in scholarly or legal settings. But do we have the death of this kind of reading performance today? I don’t think so (I’d also note that scholastic argumentation is hardly the only mode of reading past or present).

Ok, so I don’t think anything like the death of the book can be pronounced because I don’t think there is a thing called “the book” that was born and could die.

It might be possible to follow the “programs” of the book and how they have enabled different processes and performances and this is worth doing. But it’s not what you’ve asked me to do here, so I’ll transition to thinking about the affordances of our current digital media technologies and their relations to this nexus of activity signaled by our colloquial reference to “the book.”

So what can we say about the affordances of digital “dynamic knowledge systems” that (like books) are “organized and structured to allow various routes of access”? A lot, I imagine. Again, I think a great deal of our understanding of the affordances of media depends on understanding the systems of which they are part and on understanding reading as a performative and generative act. For the sake of this discussion, let’s limit the possibilities to thinking about how digital knowledge systems can be of use for academic performances – both critical and creative.

Jonathan Sawday talks about “correction and improvement” as affordances of early modern print – a kind of stable or fixed text could be released, which would then allow for improvement in subsequent editions or with new innovation.[7] According to this argument, the fixed text was a way to freeze knowledge or a design or a memory in one form such that it could then be intentionally altered (rather than spending a bunch of time and energy on ensuring its accuracy).

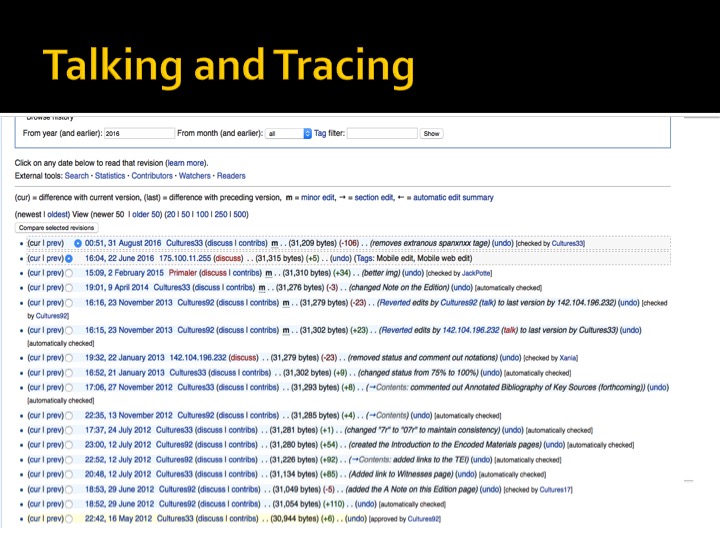

This is a feature that I think we see even more strongly in digital environments; once published to the web or in some other digital format, electronic docum ents can be continually reconfigured – both form and content can change. This means that the “program” of the text, to use Drucker’s term, can be repeatedly altered thereby producing new readings, new performances. Additionally, with tools like version control such as we see in wikis or on github we can track changes rather rapidly, which anyone working on a critical edition can attest is long and slow process in print.[8] In the case of a publication like Wikipedia or if you prefer a more scholarly example the Devonshire Manuscript Social Edition you have an interface that offers the entire history of revision and it makes iteration of the text legible in ways that would be quite cumbersome in a traditional codex.[9]

ents can be continually reconfigured – both form and content can change. This means that the “program” of the text, to use Drucker’s term, can be repeatedly altered thereby producing new readings, new performances. Additionally, with tools like version control such as we see in wikis or on github we can track changes rather rapidly, which anyone working on a critical edition can attest is long and slow process in print.[8] In the case of a publication like Wikipedia or if you prefer a more scholarly example the Devonshire Manuscript Social Edition you have an interface that offers the entire history of revision and it makes iteration of the text legible in ways that would be quite cumbersome in a traditional codex.[9]

The Devonshire Social Edition is a great example as well of the increased sociality that Drucker points to as an affordance of digital media.Talk pages and collaborative writing/editing are affordances of the digital to be sure. Version tracking will get you an entire history of the text rather easily. That said, I’ve done a lot of work in wiki environments and it is my experience that the average reader doesn’t know about version tracking or the talk pages. This is, in part, a design problem – how might one imagine an interface that provides access to the depth of information that is captured in discussions about the production of a text, along with the various iterations of the text, and allow for ease of use? It’s a little bit like trying to read a heavily revised manuscript in multiple hands for “just” the content.

Adding in layers of complexity changes how we understand “the text” and that is both productive and potentially frustrating. To take another popular example, shared real-time authoring/editing of a google docs document is fabulous for collaborative work but I wouldn’t want to have to read an essay in six colors with a range of comments and changes tracked as well. There is an interesting signal in the fact that many people hide the very mechanisms that allow for collaborative work when it comes time to publish.

The Debates in Digital Humanities online editions, edited by Matt Gold and Lauren Klein,  have taken a more integrated approach to making traces of reading visible in electronic space, bringing the social element of information sharing and reading into interface rather elegantly.

have taken a more integrated approach to making traces of reading visible in electronic space, bringing the social element of information sharing and reading into interface rather elegantly.

The kind of highlighting and commenting that is enacted therein is not new, as anyone who has ever checked out a marked up library book can attest, but it is considered a feature rather than damage in the digital context and it can unfold both synchronously and asynchronously. While I do think that increased sociality around reading, writing, and working with texts is great, I also want to point to the dangers of sociality. As the Devonshire group found, trolls can find even the most academic of projects and civility in digital spaces is no more and is perhaps even less guaranteed than it is in face-to-face interactions.

Not only does collaborative writing and editing mean that we have social networks developed and developing around digital texts, it also points to an important way in which the digital can organize labor differently than the print shop or scriptorium. Sawday argues that early modern “print as a set of technologies brought people closer together” by virtue of working in a print shop.[10] In my experience, the affordances of digital co-authorship can be quite profound.

I’ve co-written several pieces now using google docs with as many as four other authors spread over two different continents and four different time zones. The labor of production in these cases has been quite distributed and that has allowed the FemTechNet group to work as a collective and to work rather quickly despite significant distances between us. This is a real affordance. Similarly, co-authoring was possible in the past with asynchronous sharing of manuscripts or drafts, but with digital co-authoring we can leverage both synchronous and asynchronous work cycles. This is really important when juggling an array of obligations and trying to squeeze in short bursts of writing (read: great for authors with kids and lives). At the same time, I want to acknowledge that we all lament the spaces that separate us, we often wish to be together for long stretches of time, and there is a palpable sense of joy and relief when we are co-located. Distributed authoring is an affordance, but it is one that helps to solve problems that are created by our geographic distance, heavy workloads, and relative isolation as feminist scholars.

I’ve co-written several pieces now using google docs with as many as four other authors spread over two different continents and four different time zones. The labor of production in these cases has been quite distributed and that has allowed the FemTechNet group to work as a collective and to work rather quickly despite significant distances between us. This is a real affordance. Similarly, co-authoring was possible in the past with asynchronous sharing of manuscripts or drafts, but with digital co-authoring we can leverage both synchronous and asynchronous work cycles. This is really important when juggling an array of obligations and trying to squeeze in short bursts of writing (read: great for authors with kids and lives). At the same time, I want to acknowledge that we all lament the spaces that separate us, we often wish to be together for long stretches of time, and there is a palpable sense of joy and relief when we are co-located. Distributed authoring is an affordance, but it is one that helps to solve problems that are created by our geographic distance, heavy workloads, and relative isolation as feminist scholars.

If social editions and collaborative authoring interfaces create a greater degree of sociality, make iteration visible, and track the history of the formation of a text, they still remain rather stubbornly like our modern scholarly book with tables of contents, chapter headings, footnotes and the like. They are largely text-bound programs. In a more radical opening up of possibilities we might look at examples of multimedia authoring and think about the affordances evident there and I think Jessica M Johnson’s work in/with Tumblr and on blogs is exemplary.

https://diasporahypertext.com/

Part of what is so great about Johnson’s work for questions about the history of the book is that she explicitly names her triptych of sites Codex and there’s a real push here for us to think about the ways in which this is book-work.

Here is Johnson’s description of Codex:

“Each volume is housed on Tumblr, a social media platform in which waves of reblogs, shares, and remediation occur as posts are published and distributed among friends and followers. More than fluid, such dispersal defies the linear and stratified logic suggesting something of the communal and polyamorous reproduction of knowledge reminiscent of the cacophony of cosmologies crashing together as Africans moved among plantations societies. As a result, there is no linear here. The only logic is ritual.”

Johnson’s use of the form articulates both a political and epistemological stance – her sites enact a kind of sociality that goes far beyond what we might imagine for co-authoring in text. Her communities are represented at the bottom of the screen as shares, reuses, and like. They can operate synchronously and asynchronously, like shared authoring. Where they different from co-authoring is this: the form preserves a kind of agency and authorship embedded in the bricolage of shared posts that is fundamentally different from the merged voices of collaborative writing.

This is an instance where we see the remix and reuse that is often held up as an affordance of digital production come to the fore. Further, Johnson’s use of Tumblr is motivated by a commitment to forms that enact reproducibility – both as a citation politics (reproducing content) but also as a statement regarding access – Tumblr is widely used outside of academia and in her use generates a knowledge system that explodes the traditional boundaries of scholarly work. If, as Sawday suggests, print was a mechanism of repeatability, we can say that certain digital platforms are mechanisms of reproducibility, with the difference residing partly in the ability of reader/users to engage the media itself as creators as well.[11]

A different but equally compelling example is Whitney Trettien and Fran McDonald’s forthcoming (November) digital journal thresholds http://openthresholds.org/ (disclosure: I’m on the board), which opens with the following statement: “To read and to write is to become entangled; to allow oneself to be snagged upon or enmeshed amidst a profusion of other texts and ideas. Born of these twin entanglements, criticism is necessarily an act of collaboration between an author and a churning mass of other things.”

As Trettien and McDonald note, their interface “bears witness to the dynamic processes that constitute reading and writing by way of a split-screen digital architecture.” The goal here is to bring the gathering and collecting that many of us do as scholars and artists literally into the frame. In addition to a short essay on the left side, the right side of the screen gathers multimedia fragments to create a reading performance that must take place in the spaces in between. The thresholds interface freezes a bricolage of materials and disrupts a readers ability to perform readings dependent on the fiction of a fully formed authorial idea or stable, finished text. Instead it captures entanglement in a formal structure and eschews the directional or informational apparatus of the footnote. Johnson’s use of Tumblr enables her to aggregate and formally present the waves of remediation that hold a community together. thresholds, in contrast, aggregates materials with which the author is engaged

Again thinking about how media work rather than what they are, we might think of digital media tools like Google docs, Tumblr, and the split screen interface as weaving appliances – technologies for creating and disseminating either tightly woven (as in the google docs example) or quilted (as in Tumblr or thresholds) information. For me this is a useful metaphor, but I want to signal that it misses the different temp oralities and socialities of digital creation and the iterative nature of the ever-editable program of digital publishing.

oralities and socialities of digital creation and the iterative nature of the ever-editable program of digital publishing.

We might think through whether or not digital iteration is akin to the Odyssey’s Penelope weaving and unweaving her shroud and what that kind of unmaking and remaking means for our creative and readerly performances.

Prompt 2: In what ways have researchers, administrators, libraries, universities, and cultural institutions historically responded to news of the book’s demise? How can scholars engage seriously with claims regarding the declining attention spans of “digital natives,” or with the waxing and waning fortunes of MOOCs (massive open online courses) and flipped classrooms? How, if at all, should the book’s supposed decline inform the mission of higher education and its role in public discourse?

Response: A survey of the many ways that people in higher ed and cultural institutions have responded to the supposed death of the book would take more time than I have here. That said, there are some familiar tropes including that of the “digital native,” the lament for the lost good old days of long form reading, critiques of popular culture as fluff or distraction, and a lot of handwringing about the kinds of technologies that we should have in our classrooms and homes – whether they be books or phones that play Pokemon Go. We could read all of this as symptomatic of one or another cultural anxiety and generational shift. I’ll be brief and say that I think hysteria is misplaced and dismissal of students is a terrible pedagogical approach.

Wendy Chun does a fabulous job talking about the ways that the purported speed of new media are part of the rhetoric of new media itself – this idea that we’re always struggling to catch up and that none of this has ever been experienced before is part of the market cycle of planned obsolescence and the very idea of “the new.”[12] I think it is precisely the job of higher education and cultural institutions to help people make sense of socio-cultural-technical changes. Rather than lament or panic, I think we do well do offer our attempts to historicize, contextualize, and render the differential impacts of socio-technical change legible. Corporations are moving rapidly to encourage a consumer who uses rather than creates and I think we have a social imperative to intervene. I also think – and I’m drawing on Johnson’s work again here – that we have a social justice imperative to push against the “strategic amnesia of digital culture” and the claims to totalizing knowledge through computational prosthetics.[13] This is actually one of my major interests – remaining productively skeptical of the total knowledge project that has been critical to the rise of first the book as “ an extra-somatic information store,’ a prosthetic memory tool which works as an ‘artificial substitute for a function that was previously performed in the body” and then, later, the rise of computational and digital tools to achieve the same ends. [14] The drive to complete or total knowledge is at odds with a feminist commitment to situated knowledge and I think the fantasy of mastery does a lot of real damage both on the ground and in our imaginaries, particularly to those whose bodies are no longer considered valid sites of knowing – people of color, but women in particular, and queer and gender non-conforming persons.

I will also say that “entanglement,” which came up in the example of thresholds is an important word for me, both in terms of understanding how media operate over time (entanglement of past and present) and with respect to my own ethical obligations as a scholar (how I become entangled with knowledge systems and the people they impact).[15] Part of our important intervention should be helping people to understand how media like the book and related digital knowledge systems operate and how they formalize and enable/disable memory and creative practices. Jussi Parrika observes that “media cultures as sedimented and layered, a fold of time and materiality where the past might be suddenly discovered anew and the new technologies  grow obsolete increasingly fast.” (see Chun). Part of this is about understanding the heterogeneity of our media landscapes and uses: “new media remediates old media…but old media never left us.

grow obsolete increasingly fast.” (see Chun). Part of this is about understanding the heterogeneity of our media landscapes and uses: “new media remediates old media…but old media never left us.

They are continuously remediated, resurfacing, finding new uses, contexts, adaptations….zombie-media: living deads, that found an afterlife in new contexts, new hands, new screens and machines.” (NB: I could say a lot about the metaphor of zombies here but will save that for another time).

Prompt 3: What is the future of humanities scholarship in the age of the book’s transformation? What critical opportunities are provided by the new forms of research publication and peer review that now exist alongside the printed monograph or journal? And how can these developments contribute to the ongoing process of interrogating and expanding traditional scholarly canons, enabling new kinds of work on gender, race, ethnicity, and migration in particular?

I’m going to keep this very short since I spent a good deal of time pointing to examples earlier that I think address some of the questions posed here. I will say that digital media tools can make it possible to do better in terms of citational politics – Johnson’s publications are excellent at making clear who she is in conversation with and why. Digital media also afford opportunities to make visible that our study of words and books as knowledge systems is always entangled with our understandings and uses of other media forms as work from both Johnson and Trettien/McDonald testify. I’ve done a fair amount of publishing using the Scalar platform and I have found that the ability to bring an array of materials together can be quite powerful for reaching different audiences, including what we might think of as “the general public.”[16] At the same time, both of my projects in Scalar have raised really thorny and urgent issues for me around cultural appropriation, centering of marginalized voices, the politics of access and reuse, and ethical questions for digital archives. I think there is a great deal of potential for reaching more audiences and in different ways. The power of the non-linear or fluid knowledge system is non-trivial and deserves continued attention. I think there are opportunities for performing with very different kinds of digital “programs” to go back to Drucker’s term. At the same time, I think there is a real risk of harm and of further entrenchment of social and economic divides. This is where I think entanglement as an articulation of an ethical commitment is useful – I am entangled with those whose words and images I leverage in digital publication and in that entanglement we are all transformed and we are all responsible.

[1] 4, also cited in Jeremy Norman’s History of Information http://www.historyofinformation.com/narrative/roll-to-codex.php

[2] Drucker 170

[3] Drucker 168

[4] Drucker 168

[5] Drucker 173

[6] Drucker 170-1

[7] Jonathan Sawday “print had the effect of freezing design at one stage of its evolution, which made it easier to transmit technical knowledge “Improvement, the process by which a design or idea could be reworked so that it became more efficient, or redesigned entirely and applied to an entirely different task, paradoxically rested on that quality of fixity that seemed so unique to print (as opposed to handwritten).” Engines of the Imagination (Routledge 2007) 79

[8] Interested in tracking changes? Check out Matthew Kirschenbaum’s book Track Changes: A Literary History of Word Processing (Harvard 2015).

[9] https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/The_Devonshire_Manuscript

[10] Engines 80

[11] Engines 83

[12] see both her Updating to Remain the Same: Habitual New Media (MIT 2016) and Programming Visions (MIT 2011) for more on the speed of new media.

[13] Jussi Parikka What is Media Archeology? (Polity 2012) 161

[14] Engines 113

[15] for more on entanglement in (new) media environments see Parrika, Karen Barad Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (Duke UP 2007), and Sarah Kember and Joanna Zylinska Life After New Media (MIT 2012)

[16] scalar.usc.edu/works/the-eugenic-rubicon/ and http://scalar.usc.edu/works/performingarchive/index

[…] Doing “not being a book” […]