Let’s begin with a definition of terms:

Barad’s ideas regarding entanglement and what they mean for how we approach history and memory has been really important to my work on digital editions, archives, and collections

In this piece (which was a presentation) I’m going to do something a little bit strange and perform a fairly critical reading of a digital book project that I directed and helped to create: Performing Archives: Edward S. Curtis and the “vanishing race.” Elsewhere I’ve argued that digital edition or collection creation is a critical design process – one that entails ethical concerns and is an active and ongoing process. It is – as the yoking together of remediation, activation, and entanglement suggests – both a matter of form and content, theory and practice. In the case of this particular project there are rather complicated histories in that we largely used existing digital assets, along with new ones created from a special collections holding, and created new digital contextual content of several different types.

Here is an additional bit regarding the critical frame for my critique:

Performing Archives: Edward S. Curtis + the “vanishing race” (http://scalar.usc.edu/works/performingarchive/index)

- Funded by a Mellon planning grant focused on consortial digital humanities

- 3 month pilot project during the summer 2013

- Idea for topic arose in concert with conversations about primary material use for the Scripps College Core I course

- We wanted to demonstrate that it was possible to work with existing digital resources to build a robust pilot project that enabled curricular integration and undergraduate research. Our curricular integration entailed working with seventeen faculty teaching a first-year seminar at Scripps College to create a resource that leveraged local special collections and engaged students in a critical conversation about race, technology, and historical identity formation. The Scripps faculty selected an unusual special collections resource: one of fewer than three hundred existing complete sets of the twenty-volume The North American Indian, by Curtis. The digital humanities planning grant team agreed that the Curtis materials and their use in the Scripps course constituted an excellent opportunity to address all of our goals.

- Authored in Scalar, which is a multimodal authoring and publishing platform established by the Alliance for Networking Visual Culture at USC

- The book includes an article-length piece by artist/scholar Ken Gonzales-Day, a set of data visualization experiments by digital scholar David S. Kim and team, a scholarly essay on the media histories of Curtis’ images by media scholar Heather Blackmore, several short thematic mediations by faculty and two student researchers at the Claremont Colleges, and a detailed primer on working with tribes and tribal assets by the LIS scholar Ulia Gossart

- It includes new recordings of the disintegrating wax recordings made by Curtis, along with nearly 2,500 visual media assets and their metadata.

While technically still open for development, including by communities of readers within and outside of Claremont, project is now in a quiet phase.

The project was an occasion to work on some technical innovation for Scalar – Honeydew Interface (aka Scalar 2.0)…

They crafted what was then a new experimental interface designed to maximize engagement with a large set of visual resources. We were the first with the gallery-like view, which allows us to see the thousands of images of The North American Indian in new ways.

David Kim and I wrote about the project for the Archives Journal and highlighted the ways that we were thinking of our digital book as something that simultaneously publishes an archive and allows authors and readers to “perform archive” or enact “liveness” with the materials therein.

In particular, we were bringing the insights of feminist theory and critical race and ethnic studies to reorient the issues of archival agency, as well as consider the ways in which recent paradigm shifts in the archival practice with respect to Native American materials can contribute to the discussion in the digital humanities about issues of cultural representation and its relationships to scholarly design.

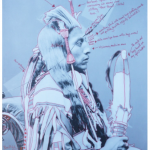

We can see this in action in Curtis’ work. As Ken Gonzales-Day reminds us in his exhibit for the book Visualizing the “Vanishing Race”: The Photogravures of Edward S. Curtis, the photographer often staged the images that he published.

Various props, like wigs or breastplates, move through multiple photographs and across tribal lines. As a work of “salvage ethnography,” The North American Indian was a production staged to argue that western tribes were in fact vanishing and that they needed to be documented for the edification of those who would remain in their place.

The archive of visual, sonic, and material culture compiled by and on behalf of Curtis was an attempt to perform an idea about Native American being, in the sense of performing his idea of what “Indianness” was. That performance continues to fundamentally shape white America’s sense of the historical place of tribal culture and practices.

Within digital humanities work, archives are regularly theorized and problematized in relation to Jacques Derrida’s “Archive Fever.” Very often the focus turns to creating pathways to wider access, establishing more inclusive canons, enhancing the search capacities of database, and anticipating the preservation challenges of our rapidly accumulating contemporary “digital cultural legacy.”

While such work broadly prioritizes the issues of scale and scalability of digital archives, we thought it was important to also recognize what “more and better” does not fully capture: the opportunity to reimagine different and differentiated archival models and practices that digital media and a performativity critique of the archive offer.

So we understood this project as something other than an essentializing access project. Thinking of “performance as critical discourse allows for focusing attention on data, not only as accumulation of cultural material, but also as a source to how data lives and operates within a culture by its actions.” Thus, performance helped us reorient away from thinking of the data that we were creating and aggregating as something upon which other forces would act and toward the idea that the data was already acting—crafting “indianness” as near absence.

Curtis’s salvage ethnography produced the sense that a remarkable array of cultures and individuals could be reduced to a history of disappearance. This required us to confront the ways that the data continued to act, both in the contexts from which we drew our materials and in the context of our digital book. Julie Louise Bacon observes that “archives express the link between ‘poesis’ as ‘the act of (history) making,’ and ‘techne’ as ‘the systemization, or industrial treatment of that act.’”

If we take the claim that our content and form – our data and technologies were always already enacting certain ideologies and subject formations seriously, then we needed to be aware of the ways in which the technologies of the archive were integral to the staging of those performances.

This means that full account of the remediations at work here would entail considering the visual and textual technologies of Curtis’s initial publication, the digital technologies that formed the basis of subsequent special collections publication at the Library of Congress and Northwestern University, and our Scalar book, as well as the media transformations that were part of the storage and sharing of the audio recordings and material culture items that we included.

We were also thinking about social networks and asking ourselves whose voices were under-represented in Curtis’ work and its reception history.

Understanding that we could not contact the more than 100 tribes represented in the North American Indian and forge meaningful relationships in our 3 month pilot, we instead undertook a study of what it would take to do such work.

We were thinking about how to engage with the issues around intellectual property rights and tribal rights – asking ourselves “who has the rights and what do we do when a “rights” framework doesn’t work for all implicated?” These are important questions that aren’t asked often enough in research – digital or analog.

So I’ve been thinking critically about activation – As Karen Barad notes, memory is not a matter of the past, but recreates the past each time it is invoked. So in this case what did we invoke? What networks were we activating? Did we really “decenter” Curtis as we’d aimed?

The large green section is the media content of the digital book – more than 2,500 assets by Curtis himself. The tiny little sliver there is one of our scholarly interventions. So, in short, no we didn’t decenter him in terms of the volume of materials (and as literary scholars we know that volume, repetition, duration matter to meaning).

However useful and interesting our essays, data viz, and photographic essays might be, they are overwhelmed in some ways by Curtis’ legacy, which we ourselves had done the work of importing. Unfortunately, we largely activated memories of oppression and settler knowledge systems.

What’s more, as the list of collaborating authors and archives suggests, we organized people working in and around centers of institutional privilege. While we were able to work more horizontally within the university systems, what we activated was an essentially privileged non-native network. Similarly, with our partner institutions we almost entirely activated networks of the state with all of their privileges and past transgressions.

Stuart Hall and Tuhiwai Smith both talk about the remarkable resilience of the western knowledge infrastructure, including archives, to assimilate/appropriate radical critique without fundamentally changing knowledge structures (46 Decolonizing Methodologies). And it seems to me that in effect, in its current state the Curtis project is a really excellent example of small and incremental difference on the top of essentially the same repressive and violent structures.

Part of Barad’s point about entanglement is that it requires us to be attentive to what gets excluded as well as what comes to matter. As noted earlier, ““monocultures produce…silences…absences.” So for me this requires that I do more to attend to the native artists who have directly engaged with Curtis’ legacy and who are not (yet) represented in the site, do more to get outside of the monoculture of white american histories.

Art by Marla Allison, Cara Romero, Virgil Oriiz, Will Wilson, Zig Jackson, and Wendy Redstar

Barad is writing here in the below about how we understand and engage the past:

So changing the past – even when that engagement hasn’t really changed much, as I think is true in this case – is never without costs, or responsibility. The production of this digital book engages in the work of invoking a particular past and that comes both with costs and responsibilities.

This is not just an theoretical issue – the book is getting used. Since January 2016 it’s had 30,000 page views, roughly 9,000 users, with roughly 20% returning (bots excluded although there are a few caveats there). Another of my projects, Eugenic Rubicon, has had about a tenth of that volume of engagement over the same period, for comparison.

I’ve not done deep analytic tracking on the site, in part because I’m generally not a fan of such tracking, so I can’t say much about who or why people are using the book. Given my own critique of the project as it stands now and the fact that it’s getting at least some usage, I find myself at a bit of juncture – a spot where I feel pretty keenly the responsibility of entanglement and activation. I’m also cognizant that there is likely to be an uptick in interest in Curtis in 2018 which is his 150 birthyear.

I’ve been thinking seriously about what should happen next. I initially felt that this project was closed for all intents and purposes, but the opportunities of talks like this and the interest in the book have me thinking about the ways I might address my own entanglement and responsibility. This has included taking the project down entirely, as well as reconfiguring it to make good on the promises of engagement and decentering. I’d welcome any thoughts/ideas you all might have. Thank you.