This is a placeholder post – one that I’m using to remind me of some thinking, writing, and making that I’d like to do in the near future.

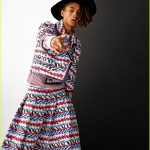

In a recent HSCollab Possibility Lunch we spent time talking about the many many different kinds of information coded in human performance/life. We were thinking through uptake of the dress-wearing of Young Thug and Jayden Smith (below)

and how we might understand these sartorial acts and their appreciation in the context of feminist theory. While some expressed discomfort with the consumerism implied therein, others felt that it was a big deal to have popular young black men publicly wearing feminized attire. As we were talking we began thinking about just how much information is encoded in the above images. The images themselves are rich, but we found ourselves reaching out into Young Thug’s lyrical work or Jayden’s social position to help us make sense of the performances. What we came to was a collective sense that we need thicker, more complex data if we really want to understand human performance and our many many vectors of meaning making. A data set that only grappled with sex and image would be really impoverished here. Imagine sentiment analysis that only took stock of the image aesthetics or short narrative responses….it would fall short, be a surface reading rather than one that positioned the men and their choices in the complex networks that help them make meaning. Even if there were thousands of images, millions even – the data set would be too small!

We realized that size does matter and that in the case of many humanistic datasets our problem isn’t that we have relatively small datasets – it’s that our datasets are really so large and so complex that they haven’t been properly understood.

Now, let me say here that I have been and continue to be a champion of the small, the seemingly insignificant, the ephemeral and boutique.

But what occurred to me as we talked the other day, was that the issue of humanistic datasets and their supposed relative smallness was actually a red herring. We have incredibly complex objects and relations to grapple with…some humanistic data might be better understood in terms of complex systems science than has been generally recognized.

Which brings me to the related topic that has been slowly simmering on a back burner with collaborators Soraya Chemaly, Latoya Peterson, and Jamia Wilson – intersectional data. We began developing this idea in July of 2015 and it continues to resonate with all of us. As I’m thinking about dataset size, three points from our notes toward an intersectional framework for data seem relevant.

- an intersectional framework insists that we cannot separate out the complexities of our identities, nor should we

- Existing concepts of multivariate data are insufficient because they don’t articulate the power relations that shape how we live, know, and are known.

- intersectional data is messy – we aren’t interested in “cleaning our data.” Data that does not reflect the realities of our identities erase those identities. It is also fundamentally inaccurate data, and when its used for any purpose, those effects are exponentially multiplied.

Essentially, intersectional data is HUGE and extremely complex. So if we are looking to create socially just data, research, and policy we should begin to get our heads around the incredible size of real human data.