What happens when we think of data “not only as accumulation of cultural material” but also as a something that “lives and operates within a culture by its actions?”[1] This is a question that motivates my work in both the history of data and quantification and cultural analysis of contemporary data cultures. Over the last 300 years we’ve seen the institutionalization of forms, metrics, and, most recently, digital work across much of the dominant American culture. As more of our everyday activities, decisions, and interpersonal interactions are being conducted digitally, our media technologies are also engaging users in highly personal and affective experiences. At the same time, the interfaces and media of quantified and digital techno-cultures promote minimalistic, one-size fits all experiences that seek to erase the interface and create the illusion of non-mediated engagement. Rather than reflect the emotional and political resonances of our quantified and digital engagements back to us, most of our media try to design away difference.

In creating haptic and sonic experiences of data for our various “Vibrant Lives” installations (Living Net, dataPLAY, and the VL sculptures) we are intervening in the sense articulated by Linda Tuhiwai Smith: “the process of being proactive and of becoming involved as an interested worker for change.”[1] In early installations this work has operated at the level of individual “data shed” or the constant streams of data we share as we use mobile devices in the United States. Our intervention is one that aims to return to individuals a tactile and memorable experience of the data that harvested silently and invisibly, tracking the most mundane of our daily activities. As we have worked on subsequent iterations, we are also working towards interventions in the deep inequality in digital cultures as well as pushing at the (academic) institutional structures that have obscured a long history of entanglement between data, computational practices, bodies, and feminized arts practices.

In particular, we are interested in taking data about our bodies (leg movements, beating hearts, shopping desires) and returning them to bodies, if only in a remediated manner. This can be done with visuals, to be sure, but there are a number of reasons why we’ve chosen not to simply make an infographic of data shed. Historically, visual media such as writing and other modes of graphic representation have been used to create and maintain data records. Similarly, our entire digital infrastructure is built upon visual, abstract, programming languages made up of computational code conventionally represented as alphanumeric symbols. Given the pervasive use of visual media in data creation and collection, the dominance of data visualization as a tool for dissemination comes as no surprise. This form of data representation is pervasive to the point that imagining data outside of a visual context as anything other than “just aesthetic” is rare.

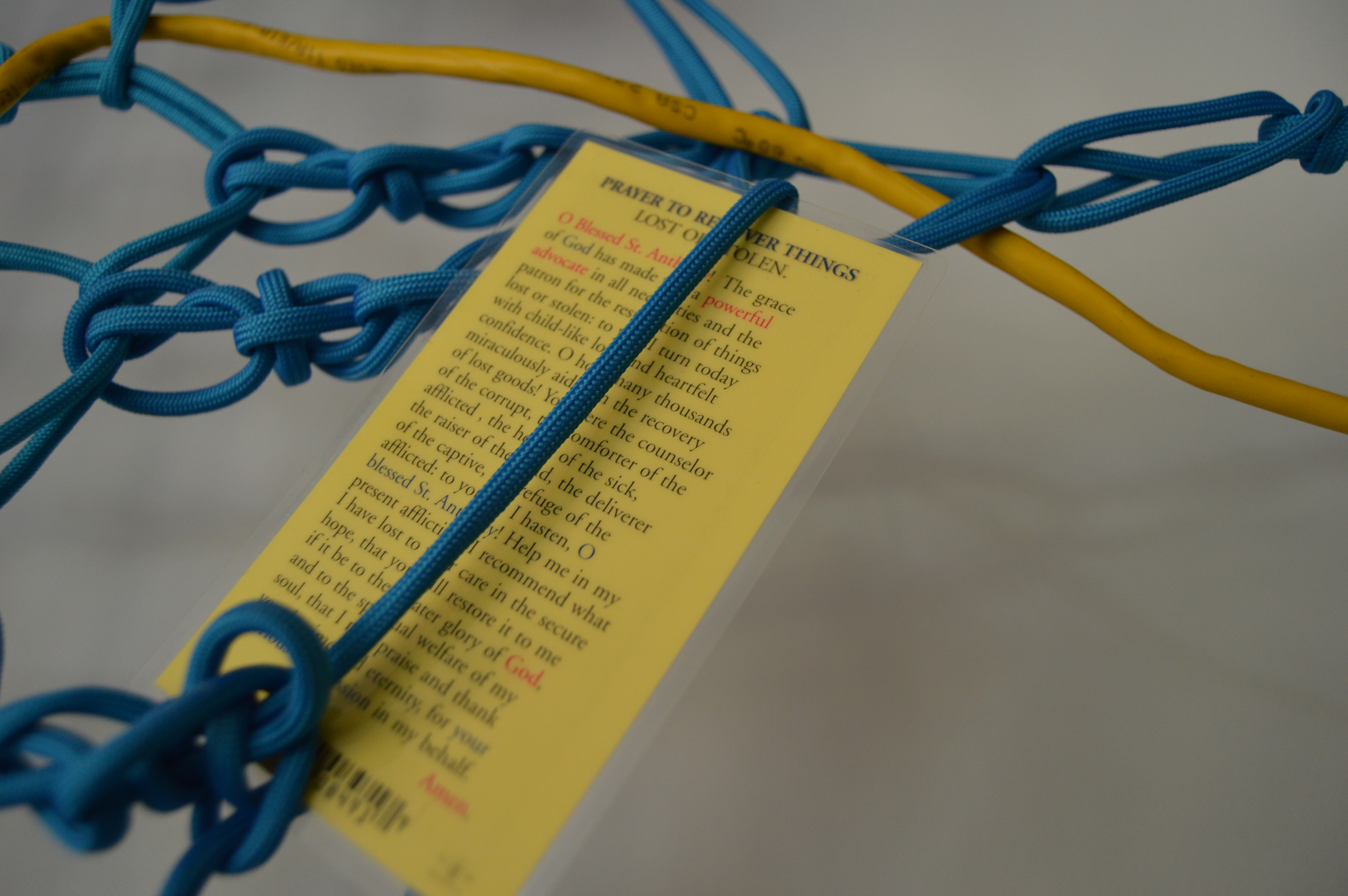

A first step in making visible the politics of activity tracking, health quantification, and mobile information harvesting is to make everyone more aware of the volume of data being gathered, how it changes with different activities on a phone or tablet device, and who is collecting and leveraging that information. Each of our installations thus far has asked people to feel and reflect on the collection of the data that shed all day long. In our most recent installations of the Living Net in both Victoria, BC and Denver, CO we’ve paired the collection and vibro-tactile representation of individual and group data shed with voluntary contributions of analog objects and metadata by our audiences. This new iteration on the original concept is designed to foreground the disparity between our largely invisible mobile data, which is highly monetized and actionable, and the tangible dust, refuse, and ephemera that we all trail behind us with little notice or care from ourselves or others. We want people to think about their own affective, epistemological, and political responses to the high value of the massive quantity of digital data and the relative lack of value attached to their analog information and objects.

[1] Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, 2 edition (London: Zed Books, 2012), 148.

[1] Gundhild Borggreen and Rune Gade (Eds), Performing the Archive (Museum Tusculanum Press, 2013).

The Living Net is an interactive data installation designed by Jessica Rajko and Jacque Wernimont, with contributions from Stjepan Rajko and Michael Krzyzaniak. The Living Net is part of the larger work of Vibrant Lives Project and has received support from Synthesis; Arts, Media, and Engineering at ASU; and the Human Security Collaboratory.

To date The Living Net has been shown by Jessica Rajko in Amsterdam, and by Wernimont and Rajko in Victoria, BC; Denver, Co; and Philadelphia, PA. Interested in hosting an installation, contact me!

Older Posts on The Living Net

The Vibrant Lives team had the great pleasure of debuting our Living Net experience Thursday evening at the University of Victoria’s Digital Humanities Summer Institute. This has been part of the ongoing and multi-faceted work of a team of artists, theorists, historians, and programmers (with some wearing multiples of those hats!).

Becoming

In a community call, we asked our distributed networks to share a piece of themselves with us.

So, in the spirit of (Carolyn) Steedman’s rag rug and other related models, I’d like to ask my “nets” – all of you who make up the networks that sustain this work – to help me weave a bit of an analog network into our vibrating, vibrant web for Vibrant Lives @ DHSI. Send me a bit, a trace, an item, a piece of your everyday and I’ll sit with it and weave it into our net at DHSI.

I was deeply touched by what arrived. People had taken seriously my invocation of Carolyn Steedman’s work in Dust and shared with us the “ends, endings, traces, and trailing” of their everyday lives; the very things that Steedman suggests are the archives where we can find those who are most often excluded from official archives and their networks of power.

I was particularly impacted by Kristina Lucenko’s mitten, which “represents the found and missing objects that make up the experience of mothering.” As she notes, by being just one of a pair the singleton also points to what isn’t seen – “..the work I should be doing – want to be doing – but instead I do the invisible work of mothering.”

The Living Net, with these belongings, records not only invisible labors, but also invisible losses — pointing to their absence and to the desires that everywhere circulate around those gaps. This is one of the ways in which I understand The Living Net to be “vibrant matter” in the sense invoked in Jane Bennett’s work. The materialist theories of both Bennett and Karen Barad have had a powerful impact on how I understand bodies – both inanimate and animate – to be involved in the work of “becoming” discussed by Sarah Kember and Joanna Zylinska in Beyond New Media. The Living Net is a way of playing with these ideas and seeing what happens we try to enact these ideas in a real-time performance with others.

Natural loss is also registered in the fragility of some of the materials. Sharon Irish shared a treasure trove of objects, including bundles of a yarn that disintegrated in my hands as I worked with it. The yarn came together with a decaying wooden spoon and as I wove these elements together and then into the net, I struggled with the losses that are a part of the passage of time – old wooden curves fell apart and slender strands shook loose. But the net(work) here still bears witness to the traces and trailings.

I spent a day crocheting and networking all of the shared belongings into what Jessica had woven beforehand. As I did so, I began to notice the ways in which the process of finger-crocheting actually recorded my own distractions; the work was tighter when I was focused, looser when I worked while talking to someone as they passed by.

I played with this a bit – laying down and moving while crocheting and paying attention to the ways that my bodily arrangement and movement was altering the knit in very subtle ways. My favorite insight from this process was the toe or foot crochet motions captured in the video below. [wpvideo TarvSI2f]

As someone who works on the history of quantifying technologies, including pedometers, turning myself into a human loom and being able to perform crocheting as step counting was fabulous fun and a productive insight into how the first pedometers (which linked a chain from a mechanical watch-type mechanism to the hip and foot of wearer) worked in practice. I can also attest that walking around results in a very irregular crochet!

It’s Alive!

The process of becoming stretched back in time to Jessica’s first crochet sessions and to the call for networked contributions. But it wasn’t completed and then shown, The Living Net depends on the engagement of our viewer/participants as well.

Embedded into the net are set of haptic devices that played the collective data shed in the room. With our extended team, we created the Vibrant Lives app to capture the number of packets being shared by people in the room via mobile devices – it’s this process that completes The Living Net performance.

This was inspired by Wendy H. K. Chun’s fantastic talks that make visible the packet transfers and the operational promiscuity involved in accessing and using the internet in traditional open networks (she also talks about this her 2011 Programmed Visions: Software and Memory). Once we “sniff” the packets we then run the numbers of either the room aggregate or individual devices through a sonification tool that renders the volume of outgoing data as sound. This is then played through the haptic devices, which are small, personal subwoofers, that essentially cause the entire net to vibrate at different rates depending on the volume of data being shed.

From Dust to Dust

Like all good things that must come to an end, The Living Net was a participatory performance and just as it came alive with the audience, it fell silent when everyone went home. We carefully unwound all of the finger crocheting that I did during the performative part of the event (I crocheted as I spoke with people, often eliciting an “oh, you’re doing it now!). We unplugged the network of belongings from the net itself and carefully stored them away for transport to a different event, a new becoming. As a performance of a network, The Living Net brought together bodies, technologies, spaces, and objects into an enactment of vibrant data. The net came alive with the connections we carried into the room with us, as well as with the interactions of our audience in real time. We activated multiple, intersecting networks for an evening and then we deactivated them as those same bodies and devices dispersed. I’ve been thinking about feminist archival work and ephemerality for some time now, and this was a great chance to think through what the ephemerality means in terms of both theory and practice.

At the same time, we are making visible the persistent traces that are a part of human-technological becoming by keeping the work we did in paracord and the yarn with which I wove together the objects in a single long strand (Jessica did the same with some of her work in Amsterdam). These persistent strands record this happening and they maintain the network of belonging that were shared for this particular call – linking people and objects in the work. They will be integrated into each future event we do with the net. In this way, we have a material archive not only of the belongings that we care for, but also of the events we make together.

The Net – which is a piece that has appeared now in two different installations, was created by one of our principals, Jessica Rajko, and first debuted in the Handmade Amplified show at 4Bid Gallery in Amsterdam.